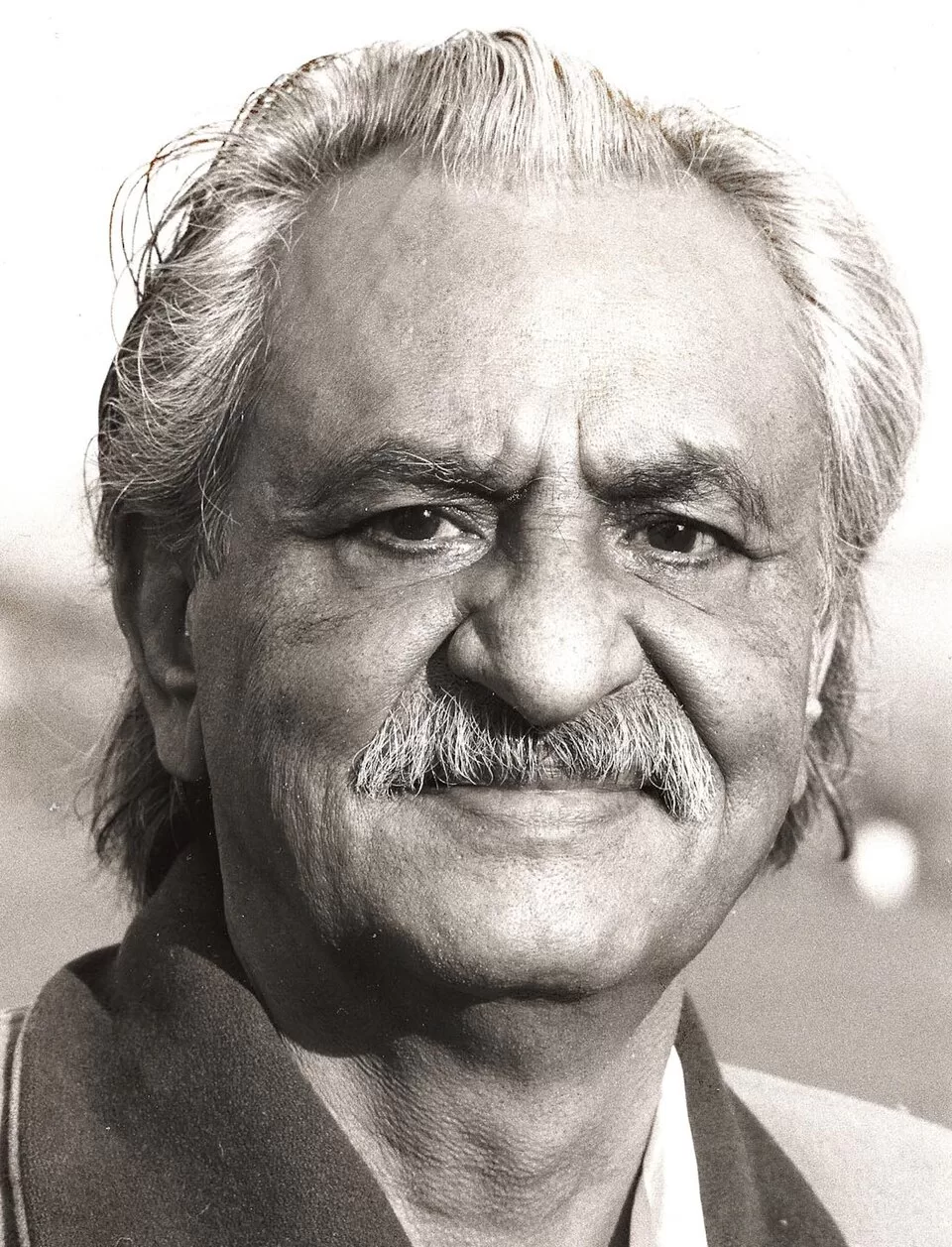

Dr. Javad Nurbakhsh

Text of a Speech for the Opening of a Three-day International Conference on “Persian Sufism: From Its Origins to Rumi” at the George Washington University.

I am delighted to have the honor of opening this conference and wish to welcome all of you. My talk today concerns the basic characteristics of classical Sufism, that is, Sufism during the first centuries of Islam. Rather than go into a lengthy technical discussion, I will attempt to provide a general outline of the key aspects of early Sufism, aspects that for the most part have been lost today.

1. A Practical and Visionary Approach to the ‘Unity of Being’

Sufi Masters of this era approached the Unity of Being from a practical rather than a theoretical perspective, through heart-insight and not the mind. Only the possessors of heart, those who have distanced themselves from the realm of self through love, are capable of gazing upon Unity with the eyes of Unity. The theoretical approach to the Unity of Being, on the other hand, is based upon a philosophy constructed by the intellect, and as such it belongs to the realm of the self.

Indeed, the theoretical approach to the Unity of Being poses many risks for those who embrace it, for one may misuse such a philosophy to justify an indulgence in various vices or offensive behavior by claiming that “all is Unity, so I can do whatever I want.” Adherence to this philosophy may actually lead to moral decay, lowering an individual from the high station of humanity.

Rumi illustrates this danger in his story of the thief who enters an orchard and steals some apricots. The owner happens to come by at that moment and seizes him. “Are you not afraid of God?” he asks the thief. “Why should I be afraid?” replies the man. “This tree belongs to God, the apricots belong to God, and I am God’s servant. God’s servant is but eating God’s property.” At this, the owner orders his servants to fetch a rope and tie the man to the tree. “Here is my answer,” explains the owner as he begins to beat the thief. In response, the thief exclaims, “Are you not afraid of God?” Smiling, the owner replies, “Why should I be afraid? This is God’s stick, the rope belongs to God, and you are God’s servant. Thus, I am only beating God’s servant with God’s stick.”

In contrast to the theoretical approach to the Unity of Being, the visionary approach is founded upon love and practiced solely by those free of self-interest. As a result, it produces guardians of society and benefactors of humanity, exemplars of human excellence, such as Abu Sa‘id Abe’l Khayr, Abo’l-Hasan Kharaqani, Bayazid Bastami, Hallaj and Ruzbehan.

The theory of the Unity of Being constitutes a philosophical doctrine. The visionary approach, however, involves a spiritual and practical path. The former is a doctrine taught and learned by the mind; the latter is a practice characterized by revelation and vision in the heart. The former increases one’s intellectual knowledge; the latter distances one from self and brings one to life in God.

When Hallaj cried out, “I am the Truth,” he was a flute being played by God’s breath. When Bayazid exclaimed, “Glory be to Me,” this was not Bayazid but God speaking through him.

2. Divine Love

The Sufi travels on the feet of love in order to reach Reality. Reason and intellect are unable to comprehend this Reality.

From the perspective of the Sufis, as long as you remain yourself, you cannot know God, the greatest veil between you and Reality being yourself. Only by the fire of divine love can this egocentricity be burned away. Moreover, such divine love arises; it cannot be learned.

Divine love may arise in the Sufi in one of two ways: through attraction and through traversing the Path. In attraction, God’s love arises within the Sufi directly, without any intermediary, and the Sufi thereby forgets everything but God. In traversing the Path, the Sufi experiences love for the Master of the Path who then transforms this love into divine love. To put it another way, the Sufi travels with and by the aid of the Master, while clutching the lamp that seeks Reality. This lamp is lit by the Master with the breath of his sacred spirit, and its flame causes the Sufi to burn with divine love. As one Sufi poet puts it:

The beings of a hundred ascetic thinkers caught fire; This is the burning we place in the crazy heart.

For Sufis, the consequence of such divine love is that they become focused solely in one direction: Sufi Masters concentrate on God alone. In the words of Khwāja ‘Abdo’llāh Ansāri, “Most people say ‘one’, yet remain attached to a hundred thousand. When the Sufis say ‘one’, however, they flee from their very identities.”

Or, as Abo’l-Hosain Nuri puts it, “The truly aware are the Sufis. Most people look to God’s bounty, whereas the Sufis look to Him alone. Others are content with His gifts; the Sufis are content only with Him.”

It is said that Rabe‘a was once asked if she loved God. “I have no love for anything else,” she replied. She was then asked if she also hated Satan. “Not at all,” was her answer, “for I am so in love with God that I have no room in my heart for hatred of Satan.”

3. The Call to Worship of God

True Masters of the Path call their disciples to God, not to themselves. Their aim is to liberate disciples from self-worship or the worship of other individuals, and to guide them to the worship of God. They do not attract others to themselves for egotistical purposes or through the display of miracles and powers. Nor do they do so for the sake of worldly gain.

‘Attār recounts the story of the son of an important figure who was one day sitting in the assembly of Abu Sa‘id. Upon hearing the Master speak, he was so struck with remorse that he repented of his misguided life and pledged everything he owned to the Master, who subjected him to several years of degrading labor. By that time, the man had become an object of contempt to the local population who rejected him. The Master then instructed the other disciples to ignore him as well. Finally, he expelled the man entirely from his assembly. Severed completely from any expectation of society, the disciple took refuge in some ruins, where he flung himself to the earth and cried out, “O Lord, You see that no one accepts me. I feel nothing any longer but pain for You, and I take refuge in nothing but You.”

After weeping like this for a time, the disciple was suddenly overwhelmed by a state which indicated that he had attained the goal for which he had striven. Back at the khānaqāh, Abu Sa‘id announced to his disciples that they should go with him to find the man he had expelled. They finally found him in the ruins, still weeping. When the disciple saw the Master, he asked him why he had been made to undergo such humiliations. “You had weaved all expectations of created being.” Abu Sa‘id replied, “but one veil yet remained between you and God: that veil was me. Now we have removed this too. Arise and return.”

4. Service to Others and Love for All of Humanity

One of the essential aims of early Sufi Masters was to encourage people to love and serve others, and to promote the development of positive qualities, setting the highest example of service to humanity themselves.

When Abu Sa‘id was asked how many were the ways from creation to God, he answered: “According to one account, there are a thousand ways; according to another, as many ways as there are created beings. But the shortest …and best way from created being to God is through kindness and service to others.”

In the words of Rumi:

Regardless of whether people accept or reject you, Serve others for the sake of God.

And in the words of Sa‘di:

True worship consists of service to others, not rosary, prayer mat and pious robe.

5. Not Being Offended by the Harassment of Others

Hāfez writes, “We keep faith, put up with blame and are glad, for on our path being offended is unbelief.” The true Sufi can never be offended by anyone. Two factors are involved here. The first relates to the Sufi’s lack of self. Being offended is an attribute of self-existence, arising from egocentricity. But the Sufi is non-existent, no one. Anyone who feels offended is conscious of having a separate existence. In being aware of both himself and God, such a person is a dualist rather than an adherent to Divine Unity. The Sufi, however, is aware only of God.

The second factor involved here is that Sufis have submitted themselves totally to God. Thus, they are content with His contentment, accepting whatever happens as coming from Him. How then could they ever feel offense? Indeed, the degree to which the traveler on the Path is offended by the harassment of others constitutes a kind of touchstone by which he or she may be judged. The more free one remains from being offended, the more liberated from self one is, and hence the more Sufi-like.

6. Chivalry

For the Sufis, chivalry has a very particular connotation. They understand it to signify the performance of altruistic service to others while remaining free of any self-consciousness with respect to the value of that service. Many Sufi Masters have spoken about such chivalry.

Abu Hafs Haddād has said, “Chivalry means being fair to others, while not expecting fairness in return.”

According to Jonaid, “Chivalry occurs without any awareness of the act of being chivalrous. The one who performs such an act never says, ‘I did this.’”

When Kharaqāni was asked about chivalry, he replied, “Were God to bestow a thousand bounties upon your brother and only one upon you, you would nevertheless give this one bounty to your brother as well.”

7. Respect for the Beliefs of Others

True Sufi Masters have always respected the followers of other religions, disapproving of disputation, prejudice and fanatical behavior in matters of religion. As Kharaqāni has put it, “Those whose hearts are engaged in distinguishing between what is right and wrong with respect to God remain far short of the goal.”

8. Self-Sufficiency, Altruism and Lack of Worldly Attachment

Among the distinctive qualities exhibited by Sufi Masters, especially those of the early period, we can also include: self-sufficiency, altruism and a lack of any attachment to worldly things (in other words, freedom from the desire for anything of the world). Selflessly committed to the service of others, these Sufi Masters possessed nothing and generously gave away to other Sufis and to the poor whatever came to them. If a Sufi had no money to give, he would bestow his cap, turban or cloak. However needy he might be materially, he would be without need spiritually. This station of self-sufficiency indicated his total detachment from all traces of existence, from all worldliness and egocentricity.

Such Sufi Masters were concerned solely with God, being detached from the world both outwardly and inwardly. Having eliminated all vestiges of self-existence, they waited patiently on the threshold of Absolute Being.

In conclusion, on behalf of George Washington University and the Nimatullahi Sufi Order, I would like to thank all the professors and scholars who graced this gathering with the results of their valuable research, thereby shedding further light on that practice of loving-kindness and true humanity that constitutes early Persian Sufism.