Originally published in Sufi Journal Issue 8 (Winter 1990-91)

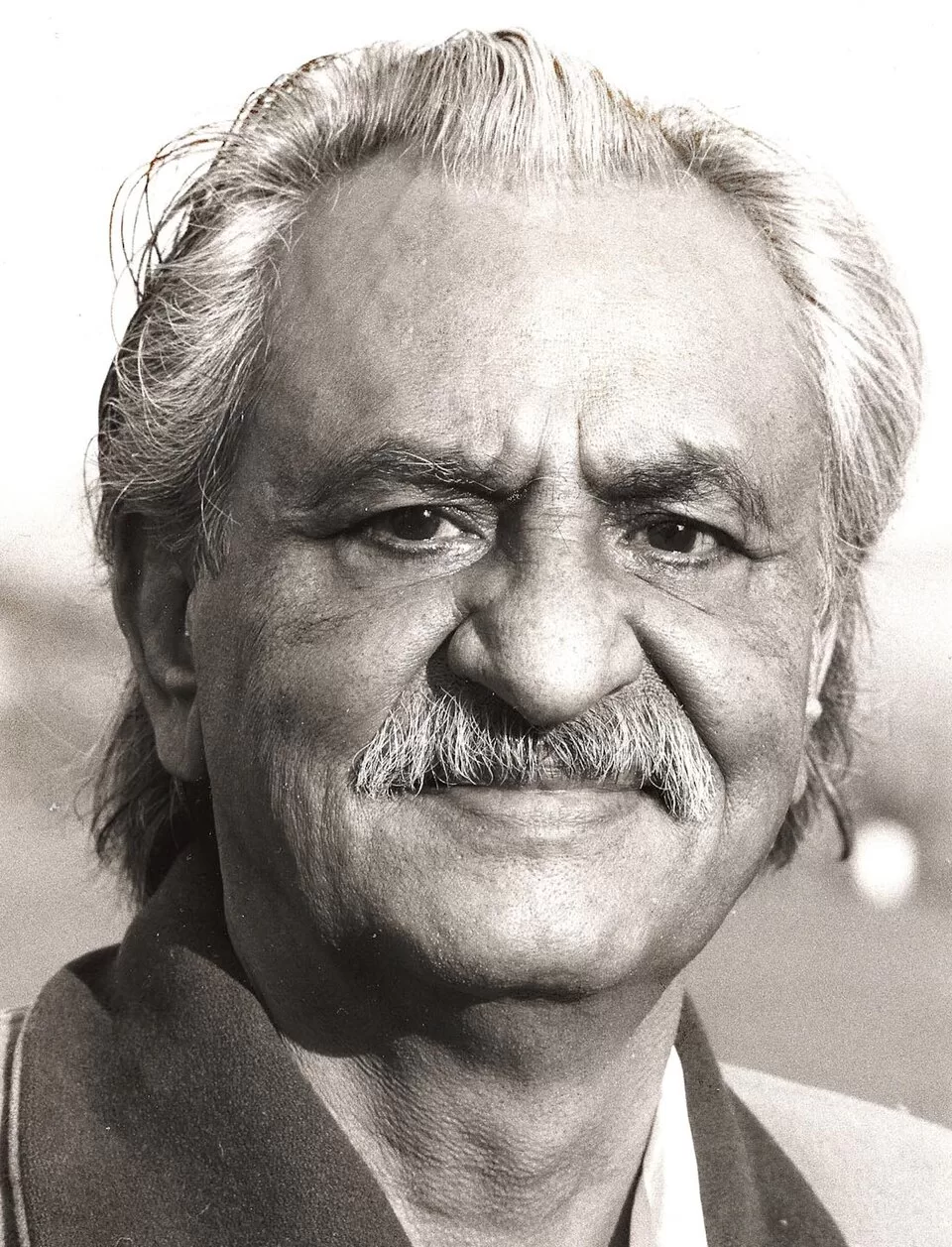

Text of a Speech by Dr. Javad Nurbakhsh, Master of the Nimatullahi Order, for the Opening of a Three-day International Conference on Classical Persian Sufism at the School of Oriental and African Studies, London University.

I am honored to open this three-day international conference on the “Legacy of Medieval Persian Sufism” which covers the three centuries preceding the Safavid period, namely, the period stretching from the beginning of the thirteenth century to the end of the fifteenth century. I am also delighted to see that the Nimatullahi Sufis have collaborated in organizing this conference. The collaboration of the Nimatullahi Research Center is very appropriate, for the Nimatullahi Order under the direction of Shah Ne’mato’llah Wali was established and formally recognized in the Islamic world during this period.

In my opening remarks, I would like to offer a few observations about two completely different approaches to the principle of the Unity of Being (wahdat-e wujud). The first is an intellectual one, while the second is founded on love. The reason for choosing this topic for the introduction of this conference is that I feel this conference is based fundamentally on an intellectual approach to various aspects of Sufism, while for me Sufism is and always has been primarily a practical and experiential school.

I assume that the participants in the conference are all aware that Sufism is principally a school of the Unity of Being (wahdat-e wujud), which can be summarized in the following way: There is only One Being and whatever exists is a manifestation or realization of that Being. As the poet said:

There is only One and nothing but Him, He is the only One and there is no one but Him.

The first question that should be raised with respect to wahdat-e wujud is whether the human intellect is capable of comprehending such a principle and ascertaining its truth. In other words, is an intellectual grasp of wahdat-e wujud possible? Modern man’s only approach to understanding the world is scientific and his only means are his own intellect and sensory perceptions. The intellect can comprehend only a realm which is based on sensory perceptions, so that the world becomes intelligible to modern man only when his sensory experience is subjected by his intellectual powers to the process of differentiation and categorization.

In order to make the world intelligible to himself, modern man constantly distinguishes certain elements from others by noting their different causal properties and associates other elements by noting their similar properties and lumping them together under one category. For example, he differentiates water from fire by citing their different causal properties, and puts ocean, river and rain under a single category by identifying the element that all these seemingly different things have in common, namely water. This process of categorization and differentiation has also been extended to encompass more abstract concepts, such as “beauty,” “justice,” “democracy,” “truth” and so forth. Man distinguishes, for example, the concept of beauty from that of justice, by contrasting the properties that one has and the other lacks, and he carries on such differentiation and categorization by scrutinizing the attributes of what he takes to be just and beautiful in the actual world.

This is how modern man makes the world intelligible to himself, and this is the only way the intellect knows how to understand something. It is an analytic approach, a rational approach, rather than the holistic, or intuitive, method, preferred by the Sufis.

Now the principle of the Unity of Being implies that whatever the human senses observe or the intellect comprehends, whether subjective or objective, is a manifestation of only One Being. How are we going to understand this? How can you and I together, along with this room and everything in it, as well as all that one can imagine or perceive, be a manifestation of only One Being? The intellect cannot see the Oneness in all creation. Why not? Because, as we mentioned, the intellect perceives things as one and the same only insofar as they have certain perceptible properties in common. For example, the intellect can ascertain the oneness of water in the various forms of river, ocean and a drop of rain, by analyzing water and discerning the one chemical substance which is shared by all the various forms of water, namely, H₂O.

Yet, one cannot comprehend the principle of Unity of Being in this manner. There is nothing perceptibly common to everything in the universe which the intellect can bring to bear in order to arrive at the principle of Unity of Being. This is where, I believe, a purely intellectual approach to the principle of the Unity of Being may lead us to skepticism and ultimately the denial of the very principle itself.

Although an intellectual and analytical approach to what the Sufis have said or written about Sufism may have historical and anthropological significance, it cannot and should not be the ultimate approach to Sufism on the part of the participants of this conference. To understand Sufism in its entirety one has to embark on the Sufi Path and be a Sufi. No one has ever comprehended wahdat-e wujud and no one has ever become a Sufi by concentrating on what the Sufis or the scholars of Sufism have said about Sufism. When Shah Ne’mato’llah says:

Wave, ocean and bubble, all three are one; There is nothing but One, no more and no less,

he is not describing an intellectual discovery about wahdat-e wujud. Rather, he is expressing his heart-findings in metaphorical terms and in poetic language. By the heart here, of course, as you all know, the Sufis do not refer to one’s “feelings,” which are usually controlled by either the passions or material reason. Rather, for Sufis, the heart refers to an organ of spiritual perception which is a gift of God’s grace and by means of which they perceive this Unity of Being.

So, what about the non-intellectual or practical approach to Sufism? First of all, let me say at the outset that without God’s grace and attention no one can embark on the Sufi Path. Only when God plants His love and the state of seeking (talab) in one, can one become a seeker who, with the help of the master of the Path, may travel the Sufi Path and ultimately experience the Unity of Being within oneself.

Traveling the Path can be both easy and difficult. There have been many who have spent a lifetime struggling with the first step on the Path, while others have completed the journey to God in a single night. The step which can be difficult for some, yet easy for others, is the annihilation of one’s self, where one’s “commanding soul” (nafs-e ammāra) is transformed into the “soul-at-peace” (nafs-e motma’enna). Those people who have been blessed by Divine grace to undertake such a step can truly comprehend the principle of the Unity of Being through direct experience and vision of the Divine.

A Sufi is one who takes this step with the foot of love and loving-kindness and under the guidance of a master who has already taken such a step. Ultimately, he leaves his self behind, transcends his ego and reaches God. We live in a period where taking such a step is harder than ever before. Modern man is more than ever attached to his ego. He is constantly trying to become something, to possess and consume, without questioning the forces that desperately drive him towards self-glorification and self-satisfaction.

I am very sure that the efforts of the scholars attending this conference have produced something which is worthwhile and beneficial to everyone, leading us to a better understanding of the historical and theoretical aspects of Sufism, but I would hope that the participants in this conference might also direct their attention to the source of all this literature: the heart. This is a path that should be traveled and experienced. Although reading the travel-documents of the prominent Sufis who have actually traveled the Path may be beneficial, it cannot take one to the ultimate goal.

In conclusion, on behalf of the Center of Near and Middle Eastern Studies of London University and the Nimatullahi Research Center, I would like to warmly thank all the participants for taking the trouble to journey from different corners of the world to attend this conference and contribute to a better understanding of the theoretical and historical aspects of classical Persian Sufism.